Disclaimer: This post is not intended to promote or discredit supernatural claims, rather it aims to look at how to examine claims of any sort.

In this article, we will take a look at:

What is evidence and proof? Are these the same?

What are the limitations of science, if any?

Claims

The British author and physician, Sir Conan Doyle, once wrote:

“When you have eliminated all which is impossible, then whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth.” (The Case-Book of Sherlock Holmes)

This is a take on the "simplicity principle," known as "Occam's razor," which states that in explaining a thing no more assumptions should be made than are necessary. Or to put it differently the simplest explanation is usually the correct one.

James Randi, the late magician and skeptic, often appeared on live TV and, applying Occam's razor, replicated feats demonstrated by psychics and others with claims tied to the "supernatural". Even under the most basic of tests—agreed upon by both Randi and the claimant—the claimants would fail to demonstrate their own ability; in some instances using nothing more than talcum powder (baby powder) or packing peanuts. Randi demonstrated when it came to the claims of those seeking the prize money he offered (in later years totalling to $1M dollars), the methods employed—rather than being supernatural—were likely natural and, oftentimes, purposefully deceptive.

Likewise, when it came to examining extraordinary claims, the astronomer, Carl Sagan stated, “What counts is not what sounds plausible, not what we would like to believe, not what one or two witnesses claim, but only what is supported by hard evidence, rigorously and skeptically examined. Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.”

Where Sagan missed the mark is that, although extraordinary claims are likely more convincing when "extraordinary" evidence is provided, it is not a necessity. Let's rephrase the last part of his quote and see how this new take is a more fair and accurate criteria for examining any claim, both ordinary and extraordinary:

"A claim—extraordinary or otherwise—requires sufficient evidence".

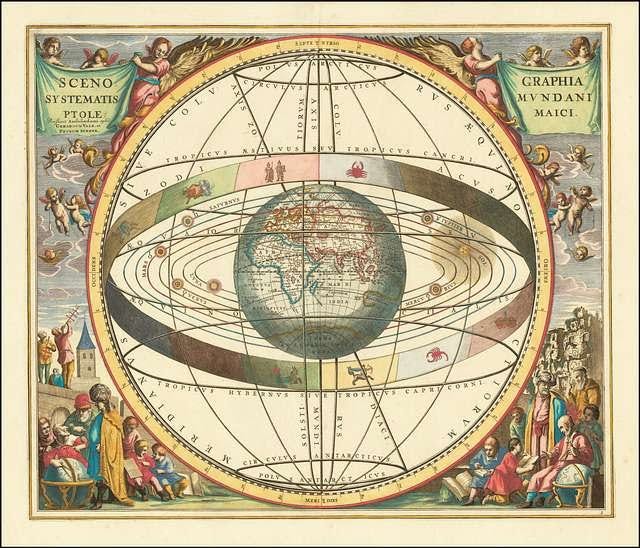

Take the Heliocentric model of the solar system, for example. This model is what we currently understand to be true—the state of all of the planets in the solar system in relation to the sun, namely that they circle or move around the sun.

Prior to this model, the belief and understanding by the scientific community and the Roman Catholic Church was that the Earth was the center of the system and the Sun and other planets moved around it. To say otherwise would have been an extraordinary claim. In fact, the Italian astronomer, Galileo Galilei, was forced by the Roman Inquisition to stop promoting this teaching and the supporting evidence as it conflicted with the teachings of the Catholic Church. Galileo was also subjected to house arrest because of his teachings until his death.

Evidence and proof

What then is "evidence," if we are wanting to find it or offer it, as Galileo did? And how does this differ, if at all, from "proof?" If we seek to find or offer evidence, we must first know what it is and is not.

Evidence is information or anything that supports a claim. This could come in the form of an argument, something physical, etc. One way Merriam-Webster's Dictionary defines evidence is: "something that furnishes proof"; for example, "testimony".

Proof, on the other hand, is the conclusion drawn from the evidence. Even then, proof is sometimes unattainable. An example of this is found in The Principia Mathematica—a three volume work on the foundations of mathematics—in which 379 pages were dedicated to attempting to prove that 1+1=2, which never conclusively proved this to be true. Similarly, Gödel's Incompleteness Theorem—a mathematical logic theorem—states that in any reasonable mathematical system there will always be true statements that cannot be proved.

This is where theories and judgment calls come into place. However, as Albert Einstein once said "No amount of experimentation can ever prove me right; a single experiment can prove me wrong."

To illustrate this point further, suppose that the claim is made that all ravens are black. You can go out and find all the ravens you can. You notice that raven after raven, indeed, turns out to be black. Then one day you notice a single white (albino) raven. This one raven disproves the claim or theory that all ravens are black, regardless how many others were counted before it. The claim can, and should, instead be adjusted to "most ravens are black" or "ravens are typically black."

Of course not all theories or claims are binary claims or absolutes. Many claims tend to fall into a "gray" area, with more degrees of uncertainty.

In Marcia Barttusiak's book, The Day We Found the Universe, Bartusiak commented on the 1920 Shapley-Curtis Debate (the Great Debate). It was a debate between astronomers Harlow Shapley and Heber Curtis on the state of the universe—including its size. Bartusiak stated, "At the end of the day, [the debate] was a wash. Everyone in essence went home maintaining the beliefs they held at the start of the lecture. The data were so muddled that Curtis and Shapley could take the same facts and arrive at completely contradictory conclusions."

As evidenced by "The Great Debate," science—the system by which information is discovered, analyzed and tested—is not the arbiter of truth. The information obtained using science has to be interpreted and theories formed.

This means that although a theory—an idea used to account for a situation or justify a course of action (Oxford Languages)—seems to have explanatory scope, or accounts for the majority of the evidence, it may not be the correct conclusion. Notwithstanding, the conclusion drawn, would be most rational to hold to until further evidence or data is provided.

The acquisition of evidence

As for obtaining evidence, in most cases, the scientific method is the "gold standard." This method is composed of a number of steps or processes, including: formulating a hypothesis, testing or experimenting, and communicating the findings.

This method is used across many disciplines. However, it is not always possible nor desirable in every case to replicate certain aspects. For example, in an investigation, it is not realistic, legal, or moral to commit a murder like the one that is being tried or investigated. Instead, forensic scientists may replicate the evidence obtained at a crime scene by using artificial means such as forensic mannequins, computer simulations, or rely on cases that have similar conditions and have previously been investigated.

As we've seen, science, in and of itself, does not prove the state or nature of a thing. Rather, science is the pursuit and application of knowledge and understanding of the physical, observable universe. In other words, it focuses on describing what typically occurs in the universe based on evidence.

There are limits to what science can explore. It cannot delve into subjective or philosophical matters, such as personal preferences or judgments. These areas require methods from diverse disciplines like psychology or sociology. Other disciplines, like historical science, encompasses fields such as history, archaeology, and anthropology.

To illustrate this distinction, consider the forensic scientist investigating a death, mentioned earlier. They can determine how the event occurred, whether it was an accident or murder based on observable evidence and facts. This 'how' aspect is within the realm of empirical science, relying on tangible and measurable data. However, understanding the 'why'—the motive or reason behind the event—requires a deeper analysis that falls into the domain of behavioral sciences, such as psychology or criminology.

Oxford mathematician and Christian apologist illustrates this further with an analogy of water boiling:

"You might well say, 'It's boiling because of heat exchange. [The] flame is the [source of] heat from [that] is [being] conducted through the metal base of a kettle and that's agitating the molecules. And therefore the water is boiling.' I might say, 'Well it's boiling because I would very much like a cup of tea at the moment.' Now that's a very simple illustration but it gets the point across that there are different kinds of explanation—one of those explanations is a scientific one, another is an explanation in terms of my volition, my agency, my desire. Now if you compare those two explanations they're completely different but they do not conflict."

This is not to suggest, by any stretch of the imagination, that one should not strive to prove or disprove claims or that the scientific method is not a tool worth utilizing. Rather, it is important to realize that science, like history, archeology, philosophy, are all pieces to a larger, more full picture of truth and the state of things.

To quote Einstein, once more, "It has often been said, and certainly not without justification, that the man of science is a poor philosopher. Why then should it not be the right thing for the physicist to let the philosopher do the philosophizing?" Albert Einstein (Physics and Reality).

Finally, to quote Bart Ehrman, a New Testament scholar and skeptic, "I do not think there is any way, given the nature of the historical discipline and the tools in the historian's chest, for a historian ever to claim that any of these [miracles] "probably" happened. Believers may think they did; nonbelievers will think they did not; and historians cannot arbitrate in that dispute [...]. What historians can say-clearly, emphatically, and with a clear conscience is that throughout history people have thought miracles happened." (The Triumph of Christianity)

Conclusion

In summary, science is only one piece of the larger picture that is the truth of a thing. Apart from mathematics, most things cannot (actually) be proven. However, given sufficient evidence, a position would be considered rational to accept, until evidence to the contrary is provided. This means each claim should be examined on its own merit.

When doing so, be sure to define and understand the terms used, and know the nature of the claim or thing being investigated and what fields of study it requires to do so.

I hope the information shared here has encouraged you to examine everything from all sides, including claims that you may come across in the news, on the web, or by word of mouth.